- What Information Do ESG Rating Agencies Collect?

- Main Problems with Data Used by ESG Rating Agencies

- The Problem with Combined ESG Ratings

- Setting Up Policies vs. Having a Truly Measurable Impact

- Biases

- ESG Ratings Divergence

- How Divergence Works

- Conclusion

The substantial increase in ESG investing urges businesses to project a positive corporate social responsibility image. The growing number of millennials joining the investment community is propelling companies to act in a way that will appeal to these younger investors, whose commitment to ethical investing is well-documented. A recent study by Morgan Stanely revealed that nearly 90% of millennial investors were interested in pursuing investments that more closely reflect the values they hold.

But how can you determine which companies are doing best in their ESG practices?

Enter ESG rating agencies, whose importance has grown in parallel with the trend of ESG investing. Collecting and aggregating data about companies, their function is to help investors in their decision-making process by singling out the businesses that are most successful in dealing with ESG issues.

However, ESG rating agencies have for a long time been the target of powerful criticism over the methodologies they employ and the subsequent results they get and present. Concerns over the inherent subjectivity of ratings due to a range of factors are continuously being voiced as it carries the risk of misrepresenting the actual picture and thus misleading investors.

What Information Do ESG Rating Agencies Collect?

ESG rating agencies painstakingly collect and aggregate a range of information on a company’s ESG performance – its own disclosures, third-party reports (e.g. from NGOs), news items, and proprietary research through company interviews and questionnaires.

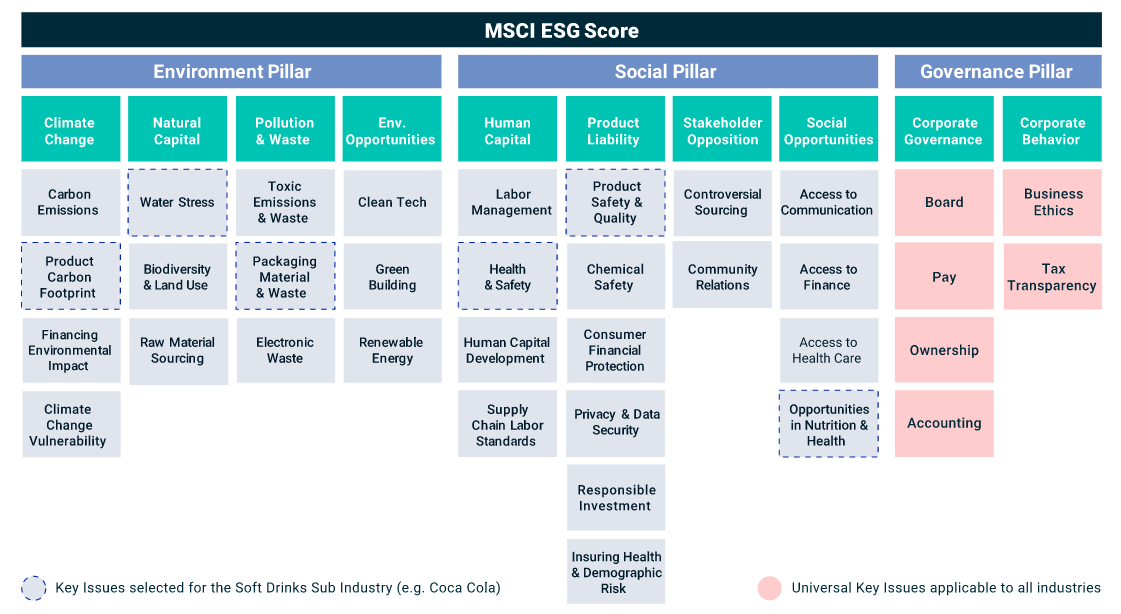

For example, MSCI assesses thousands of data points across 35 ESG Key Issues that focus on the intersection between a company’s core business and the industry-specific issues that may create significant risks and opportunities for the company. The figure below is a clear representation of the factors MSCI considers most important when rating a company.

It has to be noted, though, that every agency takes different factors into account when attempting to analyze a company’s ESG performance. In fact, the lack of standardization of the criteria used to determine a business’ rating is a common criticism leveled against these agencies.

Main Issues with ESG Ratings

Lack of quality data is traditionally identified as the main barrier to the objectivity of ESG ratings. Agencies tend to rely on self-disclosures from the rated companies or obtain data from third-party sources that is no more reliable than what firms provide themselves. Moreover, there are no legal requirements for ESG data to be audited, which leaves the door open for companies to report only the information that fits their agenda and potentially conceal some of the deficiencies in their ESG policies.

Data is self-reported

The main criticism directed towards ESG ratings is that the data used by the agencies is self-reported, i.e, the companies that appear in the tables provide the information on which they are assessed themselves.

It does not require much explanation why relying on self-reported data raises doubts over the reliability of ESG ratings. This way, companies have the freedom to pick the issues they want to be publicized and, on top of that, they can offer their own views on the subject in question. This can artificially inflate their score and make them look more ESG-conscious than they actually are.

As Alexandra Mihailescu Cichon - Executive VP at data science firm, RepRisk - recently noted, ‘self-reported data is opaquely one-dimensional and often does not account for ESG risks that have bottom-line compliance, financial, and reputational impacts for companies’.

Data is often obtained from third parties

Not only is self-reported data questionable, but ESG rating agencies also utilize data from third-party sources that may not reflect the actual results of a company’s effort within a certain field.

For instance, if a business does not report data about its water usage itself, an ESG rating agency may resort to gathering data from water utilities that contains estimates of water usage near the company’s operational sites. Whilst a resourceful method to find missing information, it by no means guarantees the veracity of this information.

Rakhi Kumar, head of ESG investment and asset stewardship at State Street Global Advisors (SSGA), commented that it is a problem that investors have to make their decisions based on incomplete information provided by a third-party, highlighting the need for companies to be mandated to self-report more accurately their ESG credentials, instead of relying on third-party providers aggregating whatever data they can get their hands on and estimating whatever data they cannot.

Data is unaudited

Furthermore, ESG data is often unaudited. Therefore, omissions, unsubstantiated claims and inaccurate figures can be hard to identify and verify within sustainability reports. From this follows that there is a major risk of presenting ratings fraught with incorrect information on which conclusions have been based.

It remains to be seen, then, if the growing pressure for more consistency among ratings will lead to requirements for firms to audit their sustainability reports. Perhaps they can take inspiration from the legal requirements they face to have all their financial statements audited by a trustworthy agency. This way, the accuracy of the information presented to the public is guaranteed. Given the rise of ESG investment, it would be in investors’ best interest if they can rely on figures that have been verified by a reputable third party.

What is more, at the end of the day, auditing does good to a company provided that it strives to operate honestly and does not want to deceive itself. Auditing helps reveal areas in which the business may be underperforming, delivering objective insight into its operations and use of resources.

There is no reason why this should exclude its ESG efforts. An independent review of its sustainability activities will give a company a different perspective and could be instrumental in optimizing its efficiency. Investors are expected to praise such an approach, too, as they want to see firms that work actively towards improving their ESG performance.

The problem with Combined ESG Ratings

The three pillars of ESG are so different from one another and contain such a broad range of factors that it is extremely challenging to interpret ratings, simply because of the way all these issues are aggregated.

For example, a company might excel in the way it ensures its employees’ health and safety, but its diversity and inclusion policies might not be as good. Yet, combined ESG ratings fail to acknowledge these nuances, instead attempting to present an aggregate score that does not really reflect the strengths and weaknesses of the business.

Jay Clayton, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission Chairman, expressed his scepticism about the value of ESG ratings at the SEC's Asset Management Advisory Committee meeting in May 2020.

He said: “I have not seen circumstances where combining an analysis of E, S and G together, across a broad range of companies, for instance with a 'rating' or 'score,' particularly a single rating or score, would facilitate meaningful investment analysis that was not significantly over-inclusive and imprecise.”

Setting up Policies is Different from Having Measurable Impact

Another common flaw of ESG ratings has been found to be the agencies’ focus on management policies and practices, rather than on the actual ESG impacts and outcomes of the companies’ assessed. Those businesses dealing with more challenging ESG issues are likely to have more developed policies and programs, but that does not guarantee that they also have the most positive impact on a specific issue.

What is more, the establishment of ESG-related policies can sometimes be associated with ‘greenwashing’, i.e., the projection of a company image more sustainable than it actually is. It is beyond doubt that more companies acknowledge ESG and it is just natural for them to start writing up policies to reflect that.

However, whilst it is fairly easy for a business to add some form of ESG commitment to its official documentation, this does not necessarily translate into a measurable result, nor is it easy to gauge its impact.

To provide an example, companies may commit to developing their workforce, but agencies seem to simply acknowledge that fact, instead of getting into detail to understand what this entails. Does it involve enrolling an employee to a course that will improve their qualifications and what benefits will this bring to them and the organization? And more importantly, how can the effect of such a step be measured?

It could indeed be difficult to gauge numerically exactly how much this employee has developed their skills and what contribution they have made to their company, hence agencies’ tendency to focus on the policy rather than the result. Yet, this approach does not show the full picture, casting doubts over the efficiency of ESG-related policies.

Company Size, Geographic, and Industry Sector Biases

Several other biases make up a few more of the reasons that render individual ESG ratings inaccurate.

A study by the American Council for Capital Formation (ACCF) published in 2018 reveals that larger companies tend to obtain higher ESG ratings, signifying the company size bias.

This could be because companies with higher valuation also have more resources to invest in measures that improve their ESG profile. As mentioned above, though, this does not necessarily mean that they also have a greater positive impact.

Unlike big companies, smaller and medium-sized ones are usually known to be more innovative, but because of their lower market cap and limited resources, they may not be looked upon favourably by ESG rating agencies.

It could well be the case that a smaller organization decides against investing in a sustainability report simply because of lack of enough human resources. Instead, this firm may choose to prioritize purely profit-making activities, which could put it at a disadvantage to its larger peers.

Conversely, if a company has the resources to invest in R&D, this can bring it ESG dividends as it may find more efficient ways to optimize certain aspects of its operations, such as energy use.

Then, disclosure requirements vary significantly by country and region, and several divergent regulatory requirements have been introduced to induce the disclosure of corporate ESG information, which may lead to geographic bias.

For example, in Europe, the EU requires companies with 500 employees or more to publish a “non-financial statement” as well as additional disclosures around diversity policy. North America has no such requirement for disclosure, which is one source for the positive bias toward European companies.

Such discrepancies may result in what seem like absurd ratings of various big corporations. A telling example would be Sustainalytics’ ratings of BMW and Tesla. The former is classified as one of the best performers (ending up in the 93rd percentile), despite a host of scandals around anti-competitive and illegal marketing practices it has been embroiled in.

On the other hand, Tesla - an electric vehicle, energy storage, and solar panel manufacturing company whose core mission is to lower CO2 emissions - was only placed in the 38th percentile.

Finally, the industry sector bias suggests that company-specific risks and differences in business models are not accurately captured in composite ratings. Rating agencies claim to normalize ratings by industry. However, more often than not, agencies assign E, S, and G weights to companies without factoring in company-specific risks. This can result in a biased rating for a company based on their industry, as opposed to company specific risks.

Let us take a look at two companies from the same industry - General Electric and Waste Management Inc. - who share the same weightings, despite drastically different ESG issue exposure.

General Electric operates as an infrastructure and technology company with eight different and wide-ranging reporting segments. The company generated 2019 revenues of USD 95 billion, both from sales of goods and from sales of services. General Electric also operates globally, selling its goods and services to an international client base.

In contrast, Waste Management, Inc., provides waste management environmental services to residential, commercial, industrial, and municipal customers in North America. The company registered 2019 revenues of USD 15 billion, generated predominantly from activity in the US and Canada.

Due to the evident difference in size and scope of operations, General Electric and Waste Management Inc. have to deal with different risk types. Yet, just because they operate within the same industry their weights and factors are applied the same, which can seriously mislead investors. The one-size-fits-all approach simplifies a way too complex topic, since potentially significant factors in their operation may be omitted.

For instance, General Electric and Waste Management Inc. may have completely different needs with regards to their supply chains. The former’s global activities gives it the opportunity to select from a broader pool of partners globally. Then, the larger resources it has access to facilitates supply chain management and enables the company to offer its suppliers more varied opportunities. At the same time, there remains the challenge of having to operate in countries that differ from each other in their application of the ESG principles.

Conversely, Waste Management Inc. probably has fewer options for its supply chain, but as its presence is confined predominantly to North America, it should stay relatively confident that it is on the same page with its suppliers, regarding regulations and best practices.

This is just one example that highlights how one aspect of a company’s operation may take different forms depending on the company’s size, current needs and goals. Alas, these subtleties are difficult to capture and analyze in greater detail, so even if one company performs extremely well in its supply chain management, if its industry peers lag behind, it may get a lower score based on the average sector performance.

The Consequence: The Troublesome Divergence of ESG Ratings

According to a research team at MIT Sloan, ESG ratings diverge substantially among rating agencies. Three scholars collaborated to prepare and publish a working paper in 2020, titled ‘Aggregate Confusion: The Divergence of ESG Ratings’. In it, they examine the disagreement among the ESG ratings of five prominent agencies around the world - KLD, Sustainalytics, Video-Eiris, Asset4, and RobecoSAM.

The research team found that the correlation among those agencies’ ESG ratings was on average 0.61. This is a rather low correlation. In comparison, the one between the credit ratings from Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s is 0.99.

Several consequences follow from the discrepancy.

First, corporate stock and bond prices are unlikely to properly reflect ESG performance as investors struggle to accurately identify out-performers and laggards.

Investor tastes can influence asset prices but only when a large enough fraction of the market holds and implements a uniform nonfinancial preference. Therefore, even if a large fraction of investors have a preference for ESG performance, the divergence of the ratings disperses the effect of these preferences on asset prices.

A study by Harvard Business School confirms this statement. It acknowledges that it is much less clear how one can or should judge the quality of ESG ratings due to their multidimensionality and the difficulty of observing clear realizations of the outcomes.

Published in 2020, the paper titled ‘Stock Price Reactions to ESG News: The Role of ESG Ratings and Disagreement’ finds that in the presence of high disagreement between raters, the relation between ESG news and market reactions weakens.

Second, the divergence can dampen the ambition of companies seeking to improve their ESG performance, due to the mixed signals they receive from rating agencies about which actions are expected and will be valued by the market.

This is an important consideration not least because it shows that not only investors, but firms as well, can be confused by the occurring divergence. It is expected of the ratings to shed light on who the true ESG leaders are and show companies what the benchmark performance is. Instead, the discrepancy between the scores assigned to one business by different agencies sends mixed signals to the company as to where it should direct its efforts henceforth.

Three types of divergence have been identified by the researchers at MIT Sloan - scope, weight, and measurement:

Scope divergence can occur when one agency includes greenhouse gas emissions, employee turnover, human rights, and corporate lobbying in its ratings scope, while another does not consider lobbying.

It implies that there are different views about the set of relevant attributes that should be considered in an ESG rating.

Weight divergence can happen when agencies assign varying degrees of importance to attributes, valuing human rights more than lobbying, for instance.

It occurs when raters use different aggregation functions to translate multiple indicators into one ESG rating. The aggregation function could be a simple weighted average, but it could also be a more complex function involving nonlinear terms or contingencies on additional variables such as industry affiliation. A rating agency that is more concerned with GHG emissions than electromagnetic fields will assign different weights than a rating agency that cares equally about both issues.

Measurement divergence occurs when ratings agencies measure the same attribute using different indicators. One might evaluate a firm’s labor practices on the basis of workforce turnover, while another counts the number of labor cases against the firm.

It implies that even if two raters were to agree on a set of attributes, different approaches measurement would still lead to diverging ratings. Measurement divergence is also partly driven by a rater effect. This means that a firm that receives a high score in one category is more likely to receive high scores in all the other categories from that same rater.

How Divergence Works

The researchers single out the ratings of Barrick Gold Corporation from Asset4 and KLD to demonstrate how wide the divergence could be. A normalized rating of 0.52 by Asset4 versus that of -1.10 by KLD reveals a significant difference in the agencies’ perception of how the company performs ESG-wise.

The 1.60 difference consists of 0.41 scope divergence, 0.77 measurement divergence, and 0.42 weights divergence. The three most relevant categories that contribute to scope divergence are Taxes, Resource Efficiency, and Board, all of which are exclusively considered by Asset4.

Then, the three most relevant categories for measurement divergence are Indigenous Rights, Business Ethics, and Remuneration. KLD gives Barrick Gold markedly lower scores for Business Ethics and Remuneration than Asset4, but a higher score for Indigenous Rights. The different assessment of Remuneration accounts for about a third of the overall rating divergence.

Finally, the most relevant categories for weights divergence are Community and Society, Biodiversity, and Toxic Spills. Different weights for the categories Biodiversity and Toxic Spills drive the two ratings apart, while the weights of Community and Society compensate part of this effect.

Conclusion

Since ESG data is extracted from heterogeneous data and varying methodologies, it is bound to diverge from one provider to another. Therefore, the informational potential of ESG scores is fairly low. Different objectives and the lack of standardized methodologies and assessments make it incredibly difficult to trust one agency more than another or to fully believe in the veracity of its ratings whatsoever.

Still, there is a silver lining in that the concept of ESG ratings is relatively young. As such, it is evolving and the issues raised in this article have been recognized. Whilst not easy to resolve, we can expect some work to be put into alleviating the problems currently associated with the ratings. Time will tell how successful these attempts will be, but, as long as it remains a central topic for investors, we believe that there is bound to be some improvement of the way companies are rated.

TenderAlpha’s database of global green public procurement contracts has been compiled using only official government sources, which guarantees the accuracy of the entries it contains. Therefore, it tackles many of the issues discussed above, offering verified information about the companies winning most green tenders. Albeit a small one, it is a step in the right direction, as it contributes to the availability of higher-quality data that can be relied upon when assessing firms.